November 2021

An opportunity to codify higher education strategy

In April 2021, the Commission on the Future of Public Higher Education, created by Act 120 of 2020 to assist the State of Vermont in addressing the urgent needs of the Vermont State Colleges and develop a vision and plan for a high-quality, affordable, and workforce-connected future for public higher education in the State, released its final report. The report finds that the Vermont legislature has long been “notably silent on what it expects out of its investments in the broader postsecondary education enterprise.” In its second recommendation, it calls on the legislature to “articulate a clear set of statewide strategic objectives for public postsecondary education […], place these in statute, and use them to direct state investments.”

At the McClure Foundation, after nearly 15 years of exclusive investment in more equitable and resilient college and career training pathways, we see an urgent opportunity and responsibility for the Vermont legislature to address that finding and to elevate the conversation to the State’s strategic objective for all aspects of postsecondary education policy and funding. Here’s why.

Why it’s important

Vermont’s public college and career training system is our greatest lever for advancing economic mobility.

Its programs and pathways support the most people in Vermont by enrollment and the most people from low- and middle-income backgrounds, for whom a credential has the biggest influence on intergenerational opportunity. The social science is clear: education and training after high school — at community, technical, and public colleges specifically — plays a vital role in any credible commitment to drive economic mobility and strengthen the middle class.

Its programs and pathways support the most people in Vermont by enrollment and the most people from low- and middle-income backgrounds, for whom a credential has the biggest influence on intergenerational opportunity. The social science is clear: education and training after high school — at community, technical, and public colleges specifically — plays a vital role in any credible commitment to drive economic mobility and strengthen the middle class.

Weaknesses in Vermont’s public college systems and postsecondary continuation are primarily a policy and funding problem — with significant ripple impacts on demographics, workforce, and poverty.

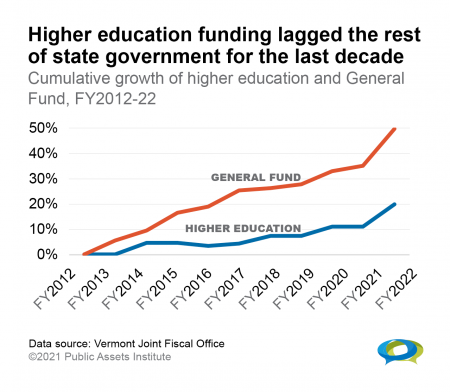

Most Vermonters know we underfund public higher education and understand how that underfunding connects to our status as a high-tuition state; many don’t realize the decades-long extent of our status nationally as an extreme outlier: we put 5% of our general fund into higher education while other states put 10% on average, and higher education spending has lagged the rest of state government spending over time. The burden of multiple decades of underfunding is held not only by the education system and its institutions, which rely more on tuition funding than any other state, but by today’s students and families who are faced with incredibly low purchasing power of Pell grants and other tuition supports. Those dollars don't go as far when state funding shifts revenue pressure onto tuition. We directly connect that legacy to the 20% differential in college continuation rates among low-income Vermont high school students when compared to their economically advantaged peers and to the fact that Vermont has the highest young adult poverty rate in New England.

The scale of funding isn’t the only problem. It’s compounded by the absence of an intentional and coherent strategy.

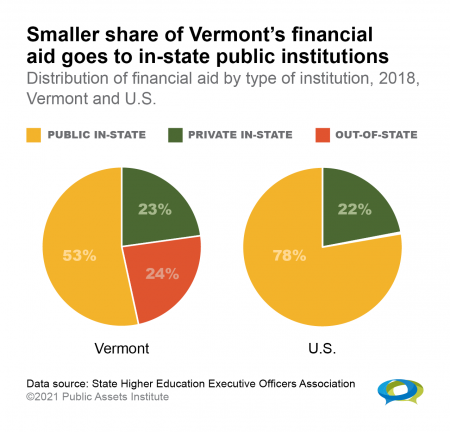

Incidents and accidents of history and politics have determined the state’s policy and funding framework for Vermont’s largest workforce development engine. Vermont spends roughly $100m/year on higher education and generally takes a “split three ways” approach to allocation of this funding between UVM, VSC, and VSAC —the last intended to be a balancing factor in a high-tuition environment. While there may have been some early intentionality, this funding structure has not been recalibrated in response to changes in impact (especially Vermont student FTE/headcount), underlying conditions, or strategic institutional or state priorities. Continued application of historic approach cements our outlier status nationally with the highest in-state public tuition at the institutions that serve low-income and first-generation Vermont students at scale — while simultaneously having the highest percentage of state aid going to send Vermonters to out-of-state institutions.

Incidents and accidents of history and politics have determined the state’s policy and funding framework for Vermont’s largest workforce development engine. Vermont spends roughly $100m/year on higher education and generally takes a “split three ways” approach to allocation of this funding between UVM, VSC, and VSAC —the last intended to be a balancing factor in a high-tuition environment. While there may have been some early intentionality, this funding structure has not been recalibrated in response to changes in impact (especially Vermont student FTE/headcount), underlying conditions, or strategic institutional or state priorities. Continued application of historic approach cements our outlier status nationally with the highest in-state public tuition at the institutions that serve low-income and first-generation Vermont students at scale — while simultaneously having the highest percentage of state aid going to send Vermonters to out-of-state institutions.

This high-tuition/high-aid approach, coupled with the “split three ways” framework, is echoed in the annual allocations generated by the Higher Education Trust Fund, which had a balance of just under $32m at the end of FY20, and in the roughly $120m allocated by the legislature to higher education in one-time pandemic funds. These and future windfalls could be leveraging a strategic priority; instead, they continue an approach that may be an attempt toward fairness (i.e. institutional parity) that in practice we believe to be a false equity frame with significant strategic opportunity costs, especially relative to long-term challenges of economic equity, demographics, and workforce.

Issues of scale and approach in state policy for higher education are longstanding and well-known.

And yet, Vermont has maintained the status quo. As summarized in a fall 2021 data and research memo generated by Public Assets Institute, several decades of consultants and commissions point to two key reasons for maintenance of both underfunding and approach:

-

Lack of clear strategy priorities for the state’s public policy and funding

-

Lack of a clear “home” in state government for higher education

While we only address the first in this white paper, we see the second as a related and critical structural problem to be considered simultaneously.

Setting the Strategy

Although we believe a clearer strategy priority for higher education policy and funding would benefit Vermont and Vermonters, we acknowledge that transitioning to a new approach will require letting go of some things we have held dear as a state. It will require leadership and a willingness to cast off a preservationist mindset. Although these up-front costs may be steep, they can purchase a future with transformative value for Vermont and Vermonters. Where we can and as we’re able, we envision shifting the conversation from preserving the status quo to dreaming together about what’s possible and embracing the change needed to get there.

Although we believe a clearer strategy priority for higher education policy and funding would benefit Vermont and Vermonters, we acknowledge that transitioning to a new approach will require letting go of some things we have held dear as a state. It will require leadership and a willingness to cast off a preservationist mindset. Although these up-front costs may be steep, they can purchase a future with transformative value for Vermont and Vermonters. Where we can and as we’re able, we envision shifting the conversation from preserving the status quo to dreaming together about what’s possible and embracing the change needed to get there.

Absent a clear home for higher education in state government, higher education policy guidance in Vermont has historically come from the institutions and organizations at the center of the state’s current approach.

Other voices, including outside policy experts and Vermont-based philanthropy, should help inform the legislature’s policy strategy development. As a long-term strategic partner and funder focused on these issues, our commitment has long been guided by clear values and a vision of what’s possible.

We see five possible strategy priorities, any of which could drive state policy and funding.

There are no doubt other options. The challenge and the responsibility of the legislature and the administration is to pick ONE — and codify it, fund it, and stick to it. Each strategy priority should lead to a different policy and funding framework.

-

Affordable pathways to promising Vermont jobs. This strategy focuses on Vermonters and prioritizes enrollment at scale at the institutions that most drive economic opportunity and equity. Successful investment will result in a significant and long-term transformation of the public’s perception of public college and career training pathways – regarding their affordability, ease of access, and connection to jobs. This strategy would charge us to think about how we can support Vermont families with the kind of affordable and accessible pathways that exist at scale in every other state. Although Vermonters’ perception of the value of college and career training was improved by pandemic-era enrollment incentives, we believe that sustaining that perception in a high-tuition state like ours will require affordability investments beyond scholarships.

-

Incentivizing relocation to Vermont. Economic and business leaders are correct in pointing out that a viable future Vermont economy relies on reversing some of our state’s pre-pandemic workforce population trends in ways that will likely require encouraging more people to move to the state. Out-of-state students at Vermont colleges are prime candidates. The State could prioritize this population, focusing on credentials in greatest need in the labor market.

-

Regional economic and cultural vitality driven by residential campuses. Regional institutions, both public and independent, are economic and cultural drivers in corners of the state that are facing substantial headwinds. The State could choose to prioritize enrollment at and maintenance of these campuses as an investment in economic, cultural, and civic vibrancy.

-

Improved research and entrepreneurial capacity. Higher education is well situated to undertake research and spur entrepreneurship in alignment with the State’s economic development interests. Public policy could prioritize research and innovation that leads to new businesses, drives job creation, and helps generate solutions to addressing complex problems.

-

Prioritizing student choice. It is to be expected that some people who grow up in Vermont will want to attend college out of state. According to Public Assets Institute, Vermont’s current aid policy is the most generous in the country for Vermont residents who choose to do so; we observe a connection to the fact that Vermont has the greatest share of postsecondary students attending college out of state. The State could choose to maintain or expand this policy.

Conclusion

We believe the time is past due for Vermont to define its core values, codify a strategic priority, and use it to chart a public funding roadmap for education and training after high school.

The challenging confluence of decades of poor public policy inflamed by the pandemic presents opportunities: strong public demand for guaranteed-affordable college and career training, renewed appreciation for the roles of government, and a shared appetite for disrupting and redesigning long-static systems and approaches in service of a more equitable and resilient future. This next legislative session is a momentous opportunity to set the strategy for the public’s investment in higher education in a way that brings the costs of that education and training into balance with the systemic role it will play in the recovery and what comes after.

Contents:

Contents: